S/V Tango. Log entries 2008-9

Part 9: Skagway to Sitka

July 26-August 15, 2009

7/27/09. We left Skagway in low clouds, drizzle, and light wind. Soon we were in fog that obscured the shore on both sides of Lynn Canal. Since there wasn’t a lot of scenery visible, I took on an odious boat chore: rebuilding the pump on the forward toilet.

Peter pumped out the holding tank and ran a lot of seawater through the toilet, then took the helm while I disassembled the toilet. I covered the table with newspaper and had plenty of paper towels ready, the parts diagram at hand, and the parts kit laid out before I took the toilet pump apart on the table.

Fortunately, the new gaskets, seals, and valves fit. I put everything back together, opened the sea cocks, and tried it. The pump worked the way it was supposed to—while it pumped sea water in to rinse the bowl, it pumped effluent out. Instead of a dozen strokes of the pump handle, only a few were needed.

We dropped the anchor in West Sullivan Island bight in hopes of catching more crabs and halibut, to no avail. In a few hours we motored to William Henry Bay, where we stayed another day. Bob again caught many crabs and a nice salmon, which we grilled.

William Henry Bay.

A school of salmon hung out at the mouth of the creek.

Bob caught a nice fish.

7/29/09. Soon after we were underway, Bob served open-faced crab sandwiches. The meat was piled high then covered with scallions and grated cheese, then broiled. What a feast. There was crab meat left over; Bob ate it like candy. He said later that it was the first time in his life when he’d had enough crab to be sated.

The sky cleared and the mountains surrounding Lynn Canal were finally visible. As we motored along in flat water, we marveled at the scenery.

That evening, at anchor in Swanson Harbor, Bob used the food chain principle to catch a lovely halibut. First he caught a little sculpin, then used it for bait. We feasted on grilled halibut steaks, refried garlic potatoes, acorn squash, and sourdough whole-wheat bread.

After dinner, Bob pulled the crab trap up and set a new CPR (crustacean personal record): 12 crabs, including eight legal-sized males. He threw most back.

Two eagles danced in flight, locking talons and doing a full roll before disengaging.

7/30/09. With a forecast of building west winds, we set off from Swanson Harbor at 08:00. We wanted to stop for provisions at Gustavus and hoped to be able to enter Glacier Bay a day early and anchor at Bartlett Cove.

Just after noon, in Icy Strait, the engine quit suddenly. It had run out of fuel, even though there was plenty of fuel in the tank. It turned out that one of the primary fuel filters was blocked, so I switched to the other filter. After I bled the system, the engine ran OK.

At Gustavus, the shore is so flat and shoal that the public dock is far from shore. It’s exposed to west winds, and when we got there we found plenty of chop. A work barge was blocking the float, so we anchored nearby amid a small school of aluminum guide boats tied to mooring buoys.

Peter and Bob rowed Clara to the dock and set off on foot to find the trading post. As they walked toward Gustavus, the air smelled like strawberries. The stopped to pick and eat a few then realized that a black bear was also enjoying the berries. They crossed to the other side of the street while the bear ignored them. Peter described the bear as being blissed out on berries.

When they got back to the dock, the wind and chop had built even more. Peter handled the dinghy well, even though it was laden heavily, and soon we were hoisting packs of groceries aboard.

As we started to leave, the engine quit just after Peter had raised the anchor. I asked him to lower it quickly and to keep the rode short. There was only a couple of feet of water under our keel and the tide was dropping. I quickly bled the fuel system again then let the engine run for ten minutes before we set off again. I had transferred all the fuel out of the starboard aft tank into the starboard forward tank and must have introduced some air into the fuel system.

Gustavus sunset.

Unfortunately, Glacier Bay had no room for us—there were as many boats in there as regulations would allow. We motored a couple of miles to a little bight off Pleasant Island and anchored for the night.

7/31/09. We motored into Glacier Bay on a rising tide and landed at the dock at Bartlett Cove in front of the Glacier Bay Lodge. While the others took showers, I cleaned the starboard aft fuel tank. After removing the inspection port on top of the tank, I peered in and saw a disgusting amount of junk in the bottom of the tank (the day before, I had transferred all the fuel into another tank). Wearing a long plastic glove, I reached in with a dish scrubbing pad and washed all the walls down, then rinsed them with the few inches of diesel fuel left in the bottom of the tank. I grabbed as much of the gunk and debris as I could, then used a portable pump to get the last of the fuel out. I also changed the engine oil and filter, then hurried off for a well-deserved shower.

We filled the fuel tanks and headed north into the bay. We soon started passing sea otters. In ten miles, we must have motored past three or four dozen otters lounging on the surface or peering at us with their cute and comical faces.

8/1/09. After a calm and quiet night in North Sandy Cove, we worked our way up Muir Inlet. We saw lots of duck-like birds, scoters and scaups, and passed through hundreds or thousands of tiny murrelets. It looked as if they were just learning to fly. Adult marbled murrelets often take off by bouncing. They’ll flap vigorously, get a few inches off the surface, then splash down and bounce up, gaining elevation to a foot or two, then sometimes bounce once or twice more before they zoom away. The little ones did more bouncing than flying—they would skitter along the surface like a skipping stone, then settle back down. Their primary evasive move is to dive, and when they do, one sees the wingtips and tail feathers last as they plunge straight down. Like penguins, they fly underwater, so their wings and body density have evolved as a compromise between flying in water and flying in air.

A water-cut valley in Muir Inlet.

We turned around at the head of Muir Inlet after paying respects to Riggs Glacier. Peter rowed Clara T and caught a bit of ice from McBride Glacier to re-stock the cooler.

Riggs Glacier

Sand piles at the face of Riggs Glacier

We anchored in the mouth of Adams Inlet. The inlet is a no-motor zone, and too shoal for Tango, but the mouth was a hospitable anchorage.

Pioneering plants, like the avens, that colonize newly-exposed glacial till often have wind-dispersed seeds.

More wind-dispersed seeds.

8/2/09. We left Muir Inlet, marveling at the hardships that John Muir eagerly endured when he explored the newly-deglaciated bay, and began our exploration of the main (west) arm of the bay. After a leisurely cruise along the shore, in a vain attempt to spot a bear or moose, we anchored in Reid Inlet, in the cool breeze off Reid Glacier. Although we saw no other boats in Muir Inlet (a few kayakers), we saw several today. We still can’t believe it’s the height of the season!

Rock scratches show the work of glaciers.

8/3/09. Bob, Jill, and I rowed ashore and walked along the beach. A rocky promontory turned us back before we got to the glacier, but we had a nice walk.

Mid-afternoon, we set out for a tour of the glaciers at the head of the bay, but our view was obscured by heavy smoke from forest fires in the interior. We spent some time in front of Lamplugh Glacier, ventured a little way toward the Johns Hopkins Glacier before turning back, and decided not to visit Margerie and Grand Pacific Glaciers. The visibility was so poor and the hour growing so late that we decided to head back toward Bartlett Cove. We worked our way among the bergy bits and growlers, sighting an occasional iceberg (defined as being 10 meters long).

Lamplugh Glacier

We motored to Blue Mouse Cove, dining on spare ribs along the way. When we got there, we found the cove empty. Again we marveled at the solitude, and noted that maybe the other boaters had been scared off. Margy and Bob had gone to the orientation when we entered the park. They reported that the rangers’ float cabin had been moved from Blue Mouse Cove because of the risk of a landslide in Tidal Inlet, right across the west arm from the cove. If the mountain slope gave way, it could create a tsunami that could inundate the cove.

Marble Island

8/4/09. We were underway before 04:00, catching the last of a favorable tidal current to boost us toward Bartlett Cove. Even though we got provisions just a few days ago, we were out of enough essentials (such as coffee and half-and-half) that an expedition to Gustavus was in order.

While I filled the water tanks, Bob and Peter caught the shuttle from the lodge into town. A little while later, Bob showed up at the dock, carrying the empty propane bottle that he’d left with.

When they got to the trading post, they found that the propane store was halfway back to the park. Bob started hitch-hiking and was picked up by the second car that passed. The driver informed him that propane was available only from 17:00 to 19:00, maybe, if the vendor wasn’t hung up at one of his other jobs. It’s just like the Gustavus liquor store, open only from 16:00 to 19:00.

The shuttle brought Peter back, with two backpacks and the wheely cart stuffed with groceries. We quickly stowed them and got underway, hoping to avoid (once again) abusing the three-hour limit at the dock.

We motored in glassy calm water and smoky skies to Fingers Bay, where we set anchor in water that was way too shallow. We were in 30 feet of water when we first dropped the anchor, but by the time we had enough rode out, we had drifted into depths of less than 10 feet. At one point one of the depth sounders read 5 feet; the other, 3.5 feet. I got out the “lead line,” a 100-foot nylon tape measure, tied a short chunk of anchor chain on as a weight, and plumbed the depths when both meters said 10 feet—the tape measure agreed.

I don’t know how we avoid going aground, but we quickly raised the anchor and eased into deeper water. Mariners beware, the chart lies. At low tide, we saw that the edge of the drying shoal extended all the way to the middle of the “6” on the chart that indicates six fathoms, or 36 feet, of water.

Salmon were jumping at the mouth of the little creek that empties into the cove. Bob couldn’t resist their siren song, so he rowed Clara T to shore to try his luck. Soon he brought back dinner—the freshest fish and the tastiest.

8/5/09. Although we knew how little water there was in the shoals, we were taken aback in the morning when we looked at the shore. Dry land was only twenty feet off our stern. The tide dropped to a -1.4 foot level, exposing the area where Bob had fished and where we had first anchored. Tango would be on her side if we hadn’t moved! Just to be safe, we shortened the rode and moved Tango further off the shore. Bob again caught a couple of fish.

We decided to head back to Bartlett Cove to try to get propane and alcohol. The smoke was so heavy that no grand vistas could be seen. The air was calm, denying any hope that a sea breeze would drive the smoke away. We got to the dock in late afternoon. Bob and Peter caught a ride on the shuttle to Gustavus and were able to re-stock the liquor cabinet and replenish the propane. After the shuttle driver dropped them off at the propane vendor’s place, they found no one home. Just before the shuttle showed up to get them, the propane guy showed up and they were able to fill the tank. We anchored out in Bartlett Cove in a very peaceful night.

Tango's travels at the northern end of the Inside Passage.

8/6/09. We left the park and motored to Inian Cove in Icy Strait. After the anchor was down, Bob put the crab trap overboard. We’d been skunked on the crabs ever since entering Glacier Bay. It could be that the resident population of 1200 crab-eating sea otters has something to do with it.

8/7/09. Alas, in Inian Cove we were not only crab-skunked, we were star-infested. When I pulled up the trap before starting the engine, it felt very heavy. When it came close to the surface, we saw that it was covered with starfish. A half dozen big sunstars and five-armed stars had wrapped themselves around the trap; they let go and fell back in the water when the trap was pulled aboard. Two big sunstars had found their way into the trap and were consuming the fish heads, their stomach everted into the bait cage. Bob feigned horror as he gingerly removed them.

When we neared South Inian Pass, we saw a number of sea lions, seals, sea otters, and humpback whales. A sea otter in Glacier Bay had returned Peter’s wave, so Margy and I waved at one lounging as we passed close by. The otter did a double-take, spy-hopped halfway out of the water, and stared intently at us. In the pass, one whale breached again and again. At least once, his whole body was out of the water, only his flukes below the surface. We watched for half an hour before we parted ways with him, still breaching in the distance.

A humpback whale breaching is like a school bus flying out of the water.

Column Point at the entrance to Lisianski Inlet.

Soon after noon we landed at the Pelican transient dock. It didn’t take long to explore all of the little town, population 180. The only street is a boardwalk; most of the buildings are on pilings over the intertidal zone. At low tide, the harbor bottom was almost covered by starfish, mostly many-armed sunstars. It’s an amazing population explosion.

Tango at Pelican

F/V Adak has seen better days.

A tent-covered wooden fishing vessel undergoes structural repairs.

Bob and Peter strolling on Pelican's main street.

The only grocery store in town was a little room in the back of a tavern, open at the whim of the staff. We got some eggs and a few other basic supplies. There’s a good restaurant, the Lisianski Inlet Café. The owners have a permit to serve fish they catch, and they are justifiably proud of the freshness of their seafood.

The fish packing plant has been closed.

A totem pole stands in front of Pelican's City Hall.

Pelican's main "street" seen from the docks.

The old and new contrast at Pelican.

8/8/09. We left Pelican, the turning point of our voyage, after staying overnight at the dock. We’re now headed for home, but we’re in no hurry. We have a week to get Bob to the Sitka airport, and we plan to dawdle. We stopped in 90 feet of water in Idaho Inlet, hoping Bob could catch a halibut, and he did. But it was too big for us, so Bob broke the line and let it go, regretting that it took his special squid lure with the hula skirt.

In Idaho Inlet, float planes met with boats from a fishing lodge to transfer passengers.

8/9/09. After a peaceful night in Inian Cove, we motored to Port Frederick and anchored in Neka Bay. The fog was thick at times, straining the nerves as we watched the radar, depth sounder, and chartplotter for hazards and other vessels. We got in late, but Bob caught a crab and a couple of small fish. I chopped vegetables while he cleaned and cooked the seafood, then he put together a wonderful seafood stew. It was so late that Peter and Margy had already gone to sleep, so they missed out.

Chimney Rock

8/10/09. We decided not to spend the night at Hoonah, a bustling Tlingit village of some 800 citizens, because the harbormaster said he’d charge extra for Clara T unless she were on Tango’s deck. Instead, we pulled up to the transient dock outside the boat basin. Almost as soon as we arrived, two humpback whales started feeding in the harbor. At first I couldn’t believe my eyes—they were within fifty feet of our moored boat. But they stayed, making bubble nets to corral schools of small fish and lunging to the surface, their mouths agape, trapping them against the surface. For the first time, I was able to see clearly the ring of bubbles rising to the surface as the whales swam in 10-meter circles beneath the fish. In less than a minute after the bubbles appeared, the giant mouths would burst from the surface.

A gaping maw breaks the surface in Hoonah Harbor.

Both whales take a big bite.

A small crowd watches from the docks.

The whales worked the harbor all afternoon. Boats, including Tango, moved cautiously to the edge of the basin and idled through. A dozen kayaks emerged as a tight flotilla and stayed close to the shore to watch. The docks and floats were lined with people who cheered when a particularly good show occurred.

A humpback does a headstand in shallow water.

Hoonah, Alaska.

Man's best friend has his own PFD.

The Hoonah Trading Company

After taking on fuel, groceries, and hardware from the well-stocked Hoonah Trading Company on the wharf, and water from the dock in the boat basin, we made our way out of Port Frederick and anchored in Spasski Bay. The sea was calm, the forest fire smoke gone, and rain prevailed.

8/11/09. We did a split day today—we got up early (04:30) and were underway at the first light. We were hoping to ride a favorable current and avoid the southerly wind predicted for Chatham Strait, but our hopes were dashed by the headwind, chop, and contrary current we encountered as we left Icy Strait. With our speed over ground sometimes below 4 knots, we decided to make a five-hour stop at Pavlof Cove to wait for the tide to turn and the breeze to die. I baked oatmeal-chocolate-chip cookies and parmesan-herb bread while Bob rowed ashore and caught a pink salmon.

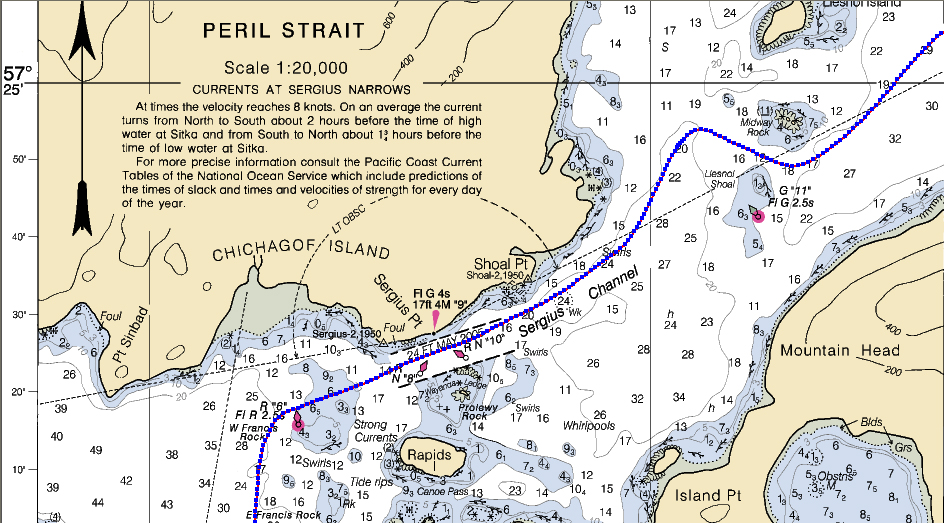

Peril, Neva, and Olga straits to Sitka.

We didn’t get into Peril Strait until just before dark. It was thoroughly dark when we entered Hanus Bay, just off Dead Tree Island. We cautiously idled in with high alert on the radar, depth sounders, and chartplotter. Peter went to the bow with a searchlight to scan for crab trap lines. Soon we were anchored in 34 feet of water. The night was very calm and peaceful, and if it hadn’t been for the current change when the tide turned, Tango would not have moved on her anchor at all.

8/12/09. We had an uneventful passage through the rest of Peril Strait, hit Sergius Narrows at slack, and anchored in St. John Baptist Bay. When he pulled up the crab trap, once again empty except for starfish and the defleshed skeletons of his bait, Bob cried out, “Crabby gods, why have ye forsaken me?”

8/13/09. We motored the few miles to Sitka and found no room at the marinas. There had been an emergency troll-fishery closure and all commercial trollers had to return to port. The docks were full. We anchored off the north dock of Eliason Harbor, waiting for a call from the harbormaster and planning to row Clara T to the dock if we had to.

While I was cleaning the dinghy, a modest fishing boat pulled away from the dock, where boats were side-tied bow to stern, packed tightly its whole length. We looked at the space it had left, uncertain whether Tango would fit. After a while, we saw a couple of men on the dock, next to the open space, waving. It turned out that they were harbormasters, but it wasn’t until they called Peter’s cell phone that we understood that they wanted us to pull in there. After our query, they said the space was probably ten or fifteen feet longer than Tango, so we decided to go for it.

Talk about docking anxiety! Not only was the space short, requiring precise parallel parking, but the harbormasters were standing by. Even though they've seen it all, they can be harsh critics of poor boat handling.

A light gust pushed Tango’s bow toward the dock as I nosed her into the space. When I saw a harbormaster put his hand on the cap rail as if to hold her off, I gunned the engine in reverse. Prop walk pivoted the stern toward the dock and the bow away. The fenders cushioned her as she slid sideways into the dock and stopped with a couple of feet of clearance astern and a reassuring amount of space ahead. I could finally breathe again.

--Dennis Todd

Photos by Dennis Todd and Peter Ffolliott.

| home | downloads and links |

| log entries | dinghy construction |

| tips for crewmembers | travel options |