S/V Tango. Log entries 2008-9

Part 4: Port McNeill to Sandspit

May 9-19, 2009

Saturday, 5/9/09. We cast off from Port McNeill in the first light of dawn and landed at the Port Hardy fuel dock before 09:30. After fueling, we planned to pump out the holding tanks but when Bob investigated he found that the pump-out didn’t work—no suction resulted when he tried the switch. Our second plan was to tie up to the docks for a few hours, wait for the turn of the tide, and check out Port Hardy. But the fuel vendor said that he’d have to charge us $10 an hour and we might have to move on a moment’s notice, so we said to hell with it. We anchored out in the harbor instead, did some boat work, and rested until it was time to go. I watched half a dozen eagles flying around the fish packing plant while others whistled from nearby trees.

The fishing fleet dominates Port Hardy. Port McNeill is a better stop for yachts.

At 16:00 we lifted the anchor and set off again to Queen Charlotte Strait and Goletas Channel. By 18:30 we were anchored in 50 feet of water at the head of Port Alexander. I got out a batch of sourdough bread batter I’d put together three days before, expecting to throw it out. But it looked serviceable after its long fermentation, so I made baguettes while Bob brewed up a batch of chicken soup. Both bread and soup were excellent.

Sunday, 5/10/09. After a quiet night, we got up early to begin a long run for Calvert Island. Even though it's exposed to the open Pacific, the water was so calm as we crossed Queen Charlotte Sound and Fitz Hugh Sound that I kneaded a loaf of bread and made a batch of raisin-oatmeal cookies.

Oatmeal-raisin cookies are out of the oven while a loaf of bread rises on the warm stove top.

Yum! Cloves and cinnamon, butter and sugar, vanilla and salt, carbs galore, all the things that make cookies delicious. I considered making a half batch, thinking that we might not consume them all before they went stale (like my cinnamon rolls—we finally fed two to the fishes), but decided to make a whole batch. I didn’t need to worry—they were gone within 24 hours.

M/V Copasetic, a yacht in the style of a North Sea trawler.

While we were motoring in Fitz Hugh Sound, we were passed sedately by a monster motor yacht. When we pulled into a cove of Pruth Bay for the night, we saw her anchored in the main bay. An hour or two later, a couple motored over in an inboard diesel RIB (rigid inflatable boat) with “Copasetic” on the side. They introduced themselves as Steven and Valerie. They brought the boat from their home in Florida through the Panama Canal and up the west coast (or their captain did) for this voyage.

M/V Copascetic in Pruth Bay.

They are planning to stay at Shearwater for a month and a half to do some fishing and exploring. We chatted about cruising the Bahamas, the dangers to yachtsmen of the drug trade in Mexico, and the taste of fresh salmon. In answer to Bob’s inquiry, Steven said that the yacht was 141 feet long and had two Caterpillar 1000-h.p. diesel engines. At 10 knots, it used 4 gallons of fuel per hour. At four or five miles per gallon, Tango doesn't do that much better.

Bob preparing to investigate crustacean life forms.

Monday, 5/11. It was a big day for Clara T—and for forward visibility on Tango. We bolted the two halves of the dinghy together on Tango's foredeck, rigged a lifting bridle, raised the whisker pole with a halyard, rigged lifting tackle, and launched her. It took a while to figure out how to set up all the rigging, but once we got it right the lift and launch went without a hitch.

Clara T towed nicely, climbing Tango’s stern wave, as we crossed Hakai Passage. It was a lively crossing, with Tango rocking and rolling in one-meter seas. It was an almost perfectly calm day, but Hakai Passage has a reputation for tossing boats about.

I tied Clara T closely to the stern as we dropped the anchor in Brydon Anchorage. I back Tango at idle to lay out the anchor rode. When I looked astern a few minutes later, I saw that Clara T was pinned broadside against the stern, with the engine exhaust dumping stinky cooling water into her. There was little I could do but go out with a boat hook and push her away as we continued to back. Once the anchor was set, I bailed her out and scrubbed her interior with Simple Green to remove the black, oily residue. Then she had her first shoreside adventure when we rowed to the shore to stretch our legs and burn our paper trash.

Burning our paper trash in the intertidal zone. Leave-no-trace boating.

Tuesday, 5/12/09. After a day’s passage of only 11 miles, we’re on the hook in “Bombproof Anchorage” in the McNaughton Group on the east side of Queens Sound. It’s a small basin with little room to swing on the anchor, but we’re closely surrounded by forested rocks that block most of the wind. Our anchor chain is hanging straight down—I think the weight of the chain is enough to hold us in place. On the GPS, it hardly looks as if we’ve moved at all.

"Bombproof Anchorage"

I rowed Clara T out the rock-choked channel that connects this basin with the open ocean (we brought Tango in the other, deeper way), bobbed around in the waves for a while, then rowed into a small cove and went ashore.

Out here at the edge of the Pacific, life is tough. In the head of a cove, ocean-bleached logs washed up on the shore show the power of the south wind. The trees are bent and twisted, shorn by the wind, many on their way to becoming emaciated grey snags.

A flagged tree clings to the rocks above the intertidal zone.

The small boat passage to the breakers.

Giant root wads washed in long ago and wedged above the high tide line have become nurse logs, each supporting a dense thicket of salal, hemlocks, cedars, mosses and lichens. Every surface above the high water line is covered with vegetation, too dense for my explorations.

A bonsai spruce growing on driftwood.

Any wood tossed above the high-tide line becomes a nurse log.

As I rowed, I marveled at how efficient a boat can be. A modest pull on the oars every six or eight feet moves me faster than I can walk. I easily bested a current that tried to sweep me back into the anchorage. Clara T tracks well but is very maneuverable. Pull one oar and push the other, and she spins in her length. It was a good thing, too, because more than once when I interrupted my rhythm and reverie to look over my shoulder to see where I was going, I found myself headed directly toward a barnacle-covered rock and had to take quick evasive action.

I baked health bread sweet rolls today. Yesterday, I made a batter of sourdough starter, whole wheat and white flour, flax seed meal, yeast and salt, and today when I kneaded it I added chopped almonds, chopped dried mangos, dried cranberries, and a cup of brown sugar. I cut the dough into rolls and baked them for 30 minutes. They are too tasty! I’m at risk of spoiling my appetite for dinner. Because Bob and I both like to cook (and to eat), we may also be at risk of porking out.

Wednesday, 5/13/09. We made 56 nautical miles of passage today, mostly exposed to the open ocean. There was just enough tail wind to make us eat our smoke as Tango rolled in 1-meter waves. During the day, as I assessed our fresh water supplies and the number of days until we’d be able to fill our tanks again, I realized that we’d better go to Klemtu instead of continuing our planned passage to Bent Harbor.

Boat Bluff light house

Boat Bluff has two resident lightkeepers. Their lives can be rich and challenging.

Klemtu is a thriving First Nations village with a recently-built long house that dominates its small bay. We landed at the fuel dock behind a fishing boat and began a conversation with Don, the maintenance worker from the fish processing plant that topped the dock. He pointed out the freshwater hose and when he heard that we needed ice, filled three buckets with shaved seawater ice from the ice house. When a man showed up to fill a car at the nearby gas pumps, I asked him about getting diesel fuel at the dock. He told me that none was available.

Klemtu fuel(less) dock. The vessel behind Tango is a seiner converted to a farmed salmon harvester. It sucks the fish out of the water, kills them within seconds with a blow to the head, and spits them out onto filleting tables. Within a few minutes, they are in the ice hold and soon, quick-frozen at the packing plant on this wharf..

The Klemtu long house is on the left.

The Klemtu long house is on the left.

I have unpleasant memories of stopping here for gas four years ago. The service was slow and surly. I concluded then that the fuel dock was managed as a convenience for tribal members. It may still be that way. We filled our water tanks and pressed on to Meyers Passage to get back west to the Outside.

Airline service at Klemtu.

A quiet evening in Meyers Passage.

The air was so still that the water was like a mirror as we anchored at the edge of Jorgenson Harbor in Meyers Passage. The line between the land and water was impossible to see except for the mirror-image symmetry. The water in our tanks was unsettling, however. When we washed dishes, it was brown and had stuff floating in it. Yuk.

Thursday, 5/14/09. We got up early but had to wait for slack at Meyers Narrows, so we began cleaning the boat. While Bob was cleaning the cockpit sole, I poured a cup of water through the filtered tap and was disgusted to see brown crud swirling in the bottom of the cup. The filter was not working. It must be time to replace the cartridge. When the unit was opened, the filter was dry and clean. It had never been wet. No wonder it wasn’t doing any good!

Barely visible atop the unit jammed under the galley counter, a valve was set on “Bypass.” Bob was able to turn it ninety degrees. After the filter element was re-installed and we flushed the tap, we had filtered water for the first time. For the past two years, we’ve been filling our tea kettle and cups with what we thought was water filtered free of most impurities, including chlorine, particles, and even giardia spores. Ah, yachting!

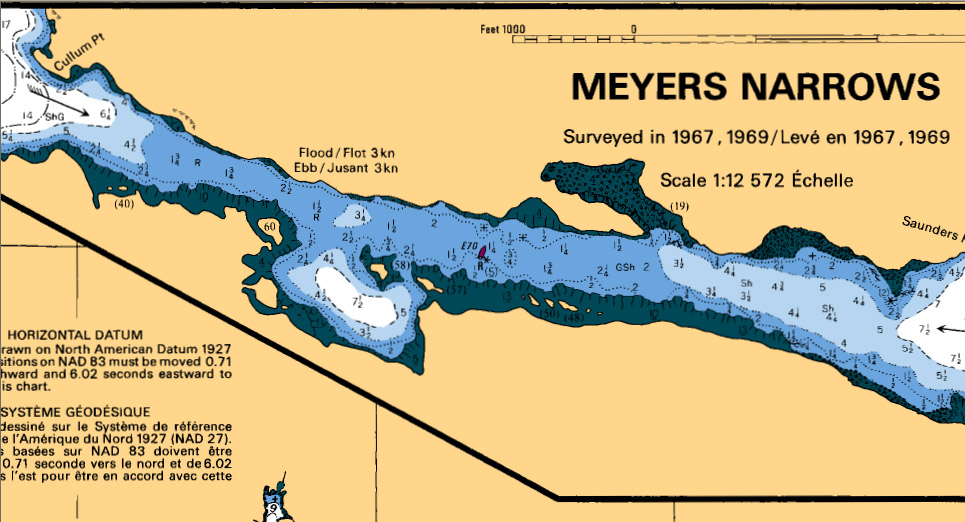

Meyers Narrows. Depths in fathoms (6 ft) at low tide.

We ran Meyers Narrows successfully near low tide. The choke point has a red buoy that marks a rock. Off the northern shore are some underwater rocks that don’t show. I decided to stay fairly close, 20 or 30 feet, from the marked rock to give us plenty of clearance for the unmarked rocks. When I looked back later at our GPS track, it looked as if we sailed right over the marked rock. Two different GPS units reported the same track. The chart must be off by at least 20 feet.

If we had followed our route exactly as it had been laid out on the chart, we would have run over the unmarked rocks. Every time we get into tight quarters, I tell Bob to steer using the terrain, depth sounder, and paper chart, not the GPS line. In some areas in the Queen Charlottes, the charts are known to be off by much more than this, perhaps hundreds of feet. The west coast of the islands is poorly charted. Many unknown hazards lurk. We’ll stay on the better-charted east coast of Moresby Island.

All day we slogged upwind, motoring at 4 to 5 knots, bumpy and rolly across Caamano Sound. The mountains get higher and steeper the further north we go. Several snowy 3000-foot peaks lie close to shore to the east of our route.

This high-speed police catamaran was the only boat we saw during our day's passage.

When we dropped our anchor in Harwood Bay, supposed to be good holding, we had a lot of trouble getting a secure set. Every time it seemed to hold, it would let go as soon as I powered up in reverse. I don’t like this CQR. I wish we had a Bruce or Lewmar Claw. We finally had to let out all 300 feet of rode in 35 feet of water and back very slowly to get it to set, and not to test it too aggressively once it set. Fortunately, the night was quiet.

Friday, 5/15/09. We were underway before 05:25, undertaking our longest day’s passage with a lot of enthusiasm and some trepidation. We were going to cross Hecate Strait. A southeast gale was forecast. The winds were predicted to be 20 to 30 knots. If the prediction comes true, we could make a 100-mile day before nightfall. I really wanted to get into the Sandspit small boat harbor while it was light enough to see.

We motored for four hours, seeing several gray whales close by and more in the distance, then raised the sails and motor-sailed for another five hours, trying to keep our speed between six and seven knots. In mid-afternoon, we finally had enough wind to shut off the engine and Tango started to fly in 20-knot beam winds. We were on first reef and reduced headsail, and probably should have been on second reef, because the 30-knot gusts made Tango round up and accelerate. I’d let her gallop off on a close reach, then when the gust eased turn her back downwind to the course.

After four hours of exhilarating sailing, we reached the waypoint at Lawn Point on Graham Island. The water in Hecate Strait is shoal, especially near Graham Island, and requires the mariner to make land ten miles north of Sandspit then sail parallel to shore, inside the shoals, to the harbor. I had a very tough time furling the genoa once we made the turn and headed upwind. The apparent wind was more than 30 knots and there was so much force on the sail as it flogged, the sheets eased, that I couldn’t pull in the furling line. I had to rig a snatch block and winch to pull it in and furl the sail.

We landed at the dock well before dark. Bob and I shared a high-five and I realized how beat I felt. My muscles ached. My shoulders were sore. My clothes were wet with rain and spray. Too much fun! I relished the sensation of having worked hard and played hard.

Saturday, 5/16/09. It seems that we’re going to be staying at this marina for a few days. They don’t make it easy to get a permit and orientation to Gwaii Haanas National Park. It took several phone calls to find that I couldn’t apply for a reservation on line or on the phone. I had to go in person to the Parks office, at the Haida Heritage Centre, to apply. The office is open only Monday through Friday. Monday is a holiday (Victoria Day), so I don’t think they’ll be open until Tuesday.

After I have a permit, I must go through an orientation, which is scheduled and delivered by a different organization. The informational packet says that 48 hours advance notice is required to schedule an orientation. I often say that sailing teaches patience. Here’s yet another example.

Irene M needs some maintenance.

Sunday, 5/17/09. After a lazy morning, we rowed Clara T a couple of kilometers to the grocery store in Sandspit. Bob took the first shift at the oars, rowing close to shore to minimize the effects of an offshore breeze. The water is so shoal that even fifty feet offshore he was grounding the oars.

Sandspit is on a low peninsula at the end of a long, shoal beach.

We bought more than a hundred dollars’ worth of groceries and as we were lugging the bags to the beached dinghy we were glad we didn’t have to carry them back to the marina. The tide had dropped even further, leaving Clara T high and dry. We had to wade out over the shoals to get into deep enough water to float her, and of course the wind had turned against us again.

It was my turn on the oars. The wind was directly from the marina, our destination. It gusted to 15 knots sometimes. As long as I kept the bow directly into the wind, I could make forward progress, albeit slowly. But when the wind caught one side of the bow, it would turn the boat and I would have to steer by reducing the power on the windward oar, slowing us badly. I wanted to stay far enough offshore that I could use the full stroke and not worry about grounding the oars, but following the wind took us farther from shore than Bob felt comfortable. I just kept pulling at the oars, trying to maintain a steady pace and a moderate level of exertion, and eventually we were back at the dock.

Sandspit small boat basin.

When loggers' boots are prohibited on the docks, you know you're in a working harbor.

The generator, lights, and seawater circulating pump ran 24 hours a day on this crabber. Bob bought a crab from them for $10.

Monday, 5/18/09. Another day at the Sandspit marina. The office in Skidegate that schedules the orientation is closed today. I hope they will waive the 48-hour-advance-notice requirement and give us our orientation tomorrow.

Sandspit Coast Guard headquarters.

Bob sweet-talked the Coast Guard staff into giving us a guided tour of their facility and their rescue boat. Unlike the U.S. Coast Guard, the Canadian CG is not militarized. Their missions include search-and-rescue and safety at sea. They do no drug enforcement, no interdiction of illegal aliens, no customs duties. They don’t carry guns. That’s the way the Coast Guard should be.

M/V Cape Mudge

When asked about what occupies their time, they responded that there is little call for rescue or assistance in these waters. All the locals know what they are doing, and the few yachts that arrive here are usually competent and prepared. They listen for the few radio calls, clean the offices, maintain the boats, barbecue dinner, and chat with visiting yachtsmen. Their schedule is 23 days on shift, 12 hours a day, and 23 days off. Our guide said it was a good life but she wasn’t sure that it would be a career. It would take a lot of sea time or four years away at the coast guard college for her to work her way up to the next grade.

We hiked the Haans Creek trail near the marina. It follows the creek through second-growth forest with giant old stumps, snags, and standing trees. It looked as if it had been a few decades since it was logged. The stumps were eight or ten feet high, and even at that height were more than four feet in diameter. One giant yew had fallen across the creek. A sign announced “Bridge.” The trail went out on the fallen log. Head down and bill cap on, I didn’t see that the trail switched to another fallen log part way across.

A fallen yew spans Haans Creek and clings to life.

I continued on the log as the trail faded and I found myself wrestling through a dense stand of small yew trees. I realized that the fallen giant was still alive. These were not young trees but adventitious branches that had sprouted and grown upright, each like a small tree. I got to the root ball and found myself fifteen feet above the stream bank. A few roots were still in the soil, but most were up in the air, some over my head. I came to the belated realization that I had lost the trail. There was no way down from my perch. I retraced my steps and found the trail again.

The amount of decomposing wood in this forest is staggering. Giant snags and decaying logs litter the landscape. The path climbs through and over long-dead wood that provides a soft, spongy tread. Trees, shrubs, mosses, lichens, ferns and liverworts thrive on nurse logs and stumps. Older trees stand on tripods of buttress roots, with hollow spaces beneath them where the nurse logs long ago disappeared.

We'll have fresh crab tonight. With any luck, we'll be headed for the park soon.

Tuesday, 5/19/09. I was finally able to get an appointment for a park orientation. Tomorrow, we'll meet across the bay at the Haida Heritage Center at 13:00. It's been a beautiful sunny day today. I occupied myself cleaning my cabin and the aft head. It's time to go for a walk.

--Dennis Todd

| home | downloads and links |

| log entries | dinghy construction |

| tips for crewmembers | travel options |